How to Handle Critique while Avoiding Soul-Death

Musicians, writers, filmmakers, artists, and other creative professionals invariably come to a point where they share drafts of their work with colleagues. You play a draft of a song for your roommate, share a draft of your novel with a trusted first-reader, show the first cut of your film to your creative partner, share a design with a client.

Then you brace yourself for their reactions.

And when early reviewers give you “notes” or other constructive feedback on your work-in-progress, they don’t typically just tell you what’s wrong. Often a reviewer will also tell you how they think you should fix the problem they identified. They tell you how they would fix it.

This is a vulnerable moment for the nascent creative seed that you have been cultivating. Critical feedback has the potential to blast the seed right out of the ground, disintegrate it, and scatter its torn fragments to the winds. To avoid this, you need an approach to receiving critical feedback.

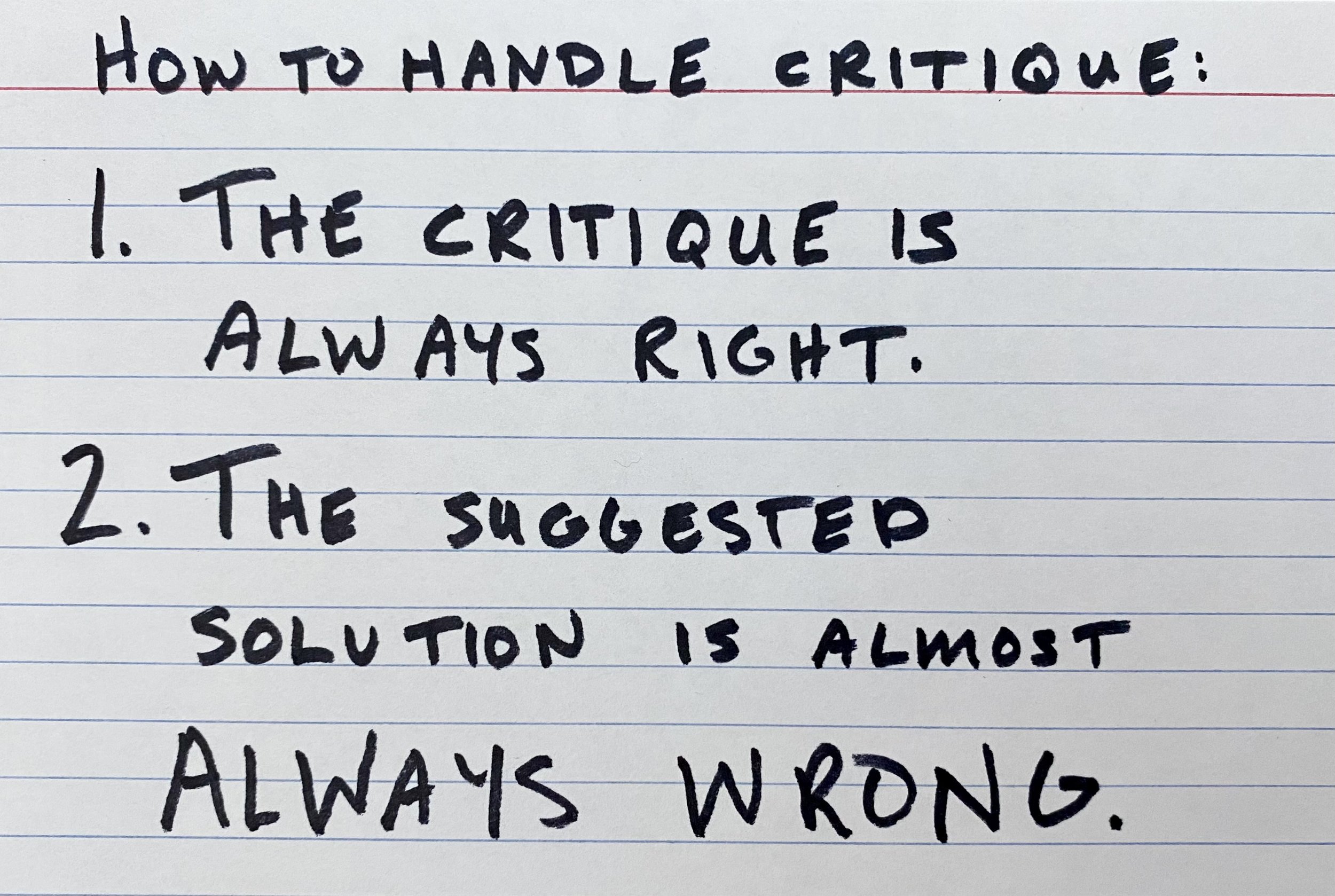

Author Neil Gaiman (Coraline, The Graveyard Book, and many others) has shared how he does it. It’s a two-part truth that you should keep in front of you at all times:

When someone critiques your work, the critique is always right. But the solution they suggest to fix it is almost always wrong.

When a director tells a film composer that perhaps they could fix the lack of energy in a scene by adding more strings, they are probably wrong.

When a producer tells a screenwriter that they should consider cutting three pages of dialogue to make the scene feel faster, they are probably wrong.

When an editor says that shifting a story’s setting from London to New York City would capture the story’s theme better, they are probably wrong.

Film composer Hans Zimmer and screenwriter Aaron Sorkin have said that they use an approach almost identical to Gaiman’s.

So if you want to utilize feedback more effectively, perhaps you can evaluate critical feedback more like Gaiman, Zimmer, and Sorkin do. You can understand that while feedback can be emotionally difficult, it is nevertheless an invaluable resource. You can remember that the most important part of the feedback you are given is the help in identifying potential problem areas in your work.

Reviewers identify problems. It’s the creator’s job to identify the solutions.

***

This article was originally sent to my email list subscribers on The Creative Process Newsletter. Put your email in the field below, or sign up here to join other creators and get insights every Monday. Want to see past editions first? Click here.